Do You

Even Know

What It

Means To be

Creative

AI has made me think a lot about creativity recently.

I co-founded and help operate a creative agency that

employs over a thousand people, all of whom identify

as "creative".

Throughout my tenure as a leader in this creative agency, I am often asked, “When did you first see yourself as a creative?” The question always strikes me as odd, as I believe that I have been innately creative all my life. From a young age, I indulged in painting and drawing, eventually developing a fascination with photography – all pursuits traditionally deemed “creative”. When I reflect on those early days of education, and even what transpires with my children’s schools today, I recognize this fundamental premise.

Children who display skills in areas like drawing, painting, writing, or performing are typically labeled as “creative”. Schools, given sufficient resources, will nurture these abilities. Conversely, children who lack such skills are deemed “not creative” and steered towards the acquisition of more practical “non-creative” skills. This dichotomy perpetuates itself in the professional world, with creative agencies or even in entertainment industries distinctly separating the “creatives” from the rest. So, it’s understandable why creatives may fear new technology: their entire self-concept, built on their unique skills, feels threatened.

In the context of AI, many have started to express apprehension, suggesting that this technology could undermine creativity. I hear many arguments against its use. Even the writers union strike has some restrictive usage of the technology to protect themselves.

It is my belief that creativity is a skill, but not a skill of the practitioner, instead a skill of thinking. AI becomes a tool to enable thinking in new and profound ways. Just like digital photography didn’t kill the discipline of photography because you can take photos on your iphone and now dodge and burn in Photoshop or use Instagram filters instead of a dark room, these new AI tools are new enablers to new kinds of creativity. But a creativity only a few people will be lucky enough to participate in. It will fundamentally change the way we think of early education and the role of creativity in business and entertainment.

This is the new reality that AI will force us to come to terms with; Not everyone is as creative as they thought. What people deemed as creative, the skill of doing something, is becoming a commodity. That creativity will go from the 1% of people who think they are creative to a new reality of maybe just .01% of people who actually are creative.

Just like traditional artists. Only a very select few get to make successful careers from making Art. There is no entitlement to the career. And just like many young adults who graduate from art schools every year but sadly cannot make a career out of their skillset, the same will be true with legacy degrees.

Andy Warhol was famous for having an entire factory executing his concepts, but he was the brain behind each unique idea. Sadly, we can’t all be Andy Warhol. And the new factory is AI, not people.

Demanding that the creative industries limit the use of AI is misguided. Not only is it virtually impossible to contain this technological advancement, but it’s also shortsighted. It’s akin to bookkeepers resisting Quickbooks due to fear of obsolescence, or coal miners protesting clean energy innovations. Imagine if we had halted the industrial revolution due to fears about job losses.

However, there is a counterargument. Creatives don’t protest against the actual innovation of AI; their objection lies in the idea that AI is a thief. It’s not about the automation of the tooling but the data AI steals from.

But as the saying goes...

Good Artists

Copy, Great

AIs Steal.

The advent of AI has shaken up traditional notions of creativity

and its value. Many fear that AI is essentially “stealing” creativity, a unique attribute that should be

fairly compensated.

The belief is that if you use a creative output to generate something new the original idea needs to be fairly compensated. After all, if someone else profits from your original idea, shouldn’t you get a share? This seems reasonable and hard to dispute.

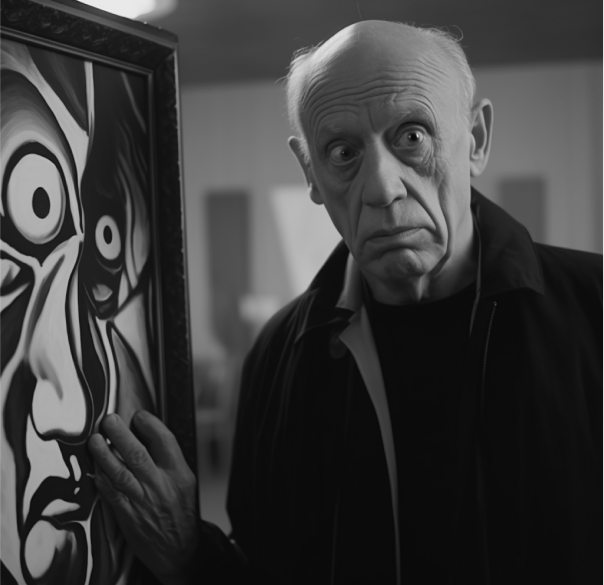

But what makes creativity unique and therefore valuable? Picasso offered a profound answer when questioned about the worth of his art.

When told, “But You Did That in Thirty Seconds.”

Picasso replied, “No, It Has Taken Me Forty Years To Do That.”

This implies that the value lies in the journey, not just the end product.

However, Picasso also famously said,

Good Artists Copy, Great Artists Steal ”

He was implying that the best creativity actually is just old creative ideas revived in a new form. Does this mean no creation is entirely original but rather a derivative of something else? If so, what does “derivative” mean in the context of creativity and human cognition?

Does the person who creates a masterpiece in what seems like thirty seconds, with each stroke backed by their life’s experience, get full ownership of that new thing? In the age of AI, that’s just a nice little anecdote. Now we’ve got machines, bereft of any life experience, churning out ‘creative’ output at the speed of light.

For centuries, humans have patted themselves on the back for their ability to take historical ideas, toss them around, and present them as something ‘unique’ and ‘original’. Conveniently, we ignore where these ideas came from, lauding the result as claimable and unique.

Consider Quentin Tarantino, who is hailed as a creative genius. He openly acknowledges the influences that shape his work. His creative process involves drawing from the past to mold his future ideas. Should he have paid the Film Noir greats some royalties because they influenced his style? If he entered a generative AI prompt instead, “in the style of Film Noir,” does all of a sudden that require a different payment for his creative influence?

Perhaps genuine creativity involves reshaping and recontextualizing historical ideas into something unrecognizable from the source. The human mind naturally (and sometimes consciously) does this. But as the origins are typically hidden, the end product is labeled as unique, inventive, original, and therefore, claimable. So, the creator retains a perpetual claim to any benefits derived from it.

But what happens when AI mimics this process of reshuffling and reconstructing ideas to produce something new? If the process is algorithmic rather than instinctual, does it strip the output of its creativity because its origins are more apparent? Is it not considered theft when a human does it, but when an AI does it, it is?

Wait... but...

What happens when AI mimics this process of reshuffling and reconstructing ideas to produce something new? If the process is algorithmic rather than instinctual, does it strip the output of its creativity because its origins are more apparent? Is it not considered theft when a human does it, but when an AI does it, it is?

Good Artists Copy, Great Artists AND AIs Steal. ”

Could it be that Picasso was wrong? Or perhaps our understanding of creativity and ownership needs reconsideration?

In the end, the great AI invasion has forced us to reassess our holier-than-thou understanding of creativity and ownership. It’s high time we stopped hiding behind romantic notions and accepted that both human imagination and AI innovation are here to co-exist, whether we like it or not.

And this old romantic notion of creativity and ownership assumes that entertainment in the future will be like today. A model where someone thinks of an idea and the idea is executed and then distributed to the masses. Maybe tomorrow, it’s the viewer that dictates what will be created, not the creator. Is this the end of the creator economy?

What happens when AI mimics this process of reshuffling and reconstructing ideas to produce something new? If the process is algorithmic rather than instinctual, does it strip the output of its creativity because its origins are more apparent?

Is it not considered theft when a human does it, but when an AI does it, it is?

This is potentially the advent of a new form of entertainment…

The Future of

Entertainment:

Do we even know

what we're

asking for?

It's Anticipatory

and Ephemeral

What happens if only one prompt ever has to be said: “Give me more value”

Remember when being the first to come up with an idea was the big deal? Everyone hailing the “genius” who thought of something new? We used to think that creativity was something valuable and special, the thing that kept us entertained.

For generations, we’ve held creativity on this high pedestal. We’ve marveled at the genius of the innovators, the artists, the disruptors. We’ve believed that creativity – the ability to generate something truly original and new – is a uniquely human trait. But let’s be real: do we even need that shiny, fresh-out-of-the-box creativity anymore? Or are we just craving the illusion of something “new and improved” to keep us entertained?

In the world of Web 2.0, personalization means leveraging location, device, and intent to tailor an experience. You could see it in Netflix’s recommendations, Amazon’s suggested products, or targeted ads. Of course, it’s all backed by those good old algorithmic engines that some may argue lack creativity. They’re just doing their job, providing value based on perceived needs.

But now, we’re venturing into a whole new territory. A world where we can prompt a system and voila – out comes something fresh, something creative. But what if these prompts weren’t manually entered? What if they were behaviorally driven, shifting and adapting to our ever-changing needs and desires? What if generative AI could whip up something personalized on the fly? It would be more than personalized, it’d be anticipatory.

Can our behaviors make us creative? Or are we just wandering in an ever-evolving maze of our own creations, no longer needing to come up with anything new? Or are we basically there now?

Imagine taking a scriptwriting class. You’d quickly become acquainted with the familiar pattern found in nearly every movie: protagonists, antagonists, story arcs, resolutions, and so forth. This formula can be identified in almost any story.

Consider Disney’s method of reusing animation, resulting in various movies with shared scenes, such as ‘Winnie the Pooh’ and ‘Jungle Book.’ Reflect on the choice to reshoot Samuel L. Jackson’s line in ‘Snakes on a Plane’ because of its anticipated impact on audiences. Many of the top hits on Fandango currently are sequels, remakes, or stories spun from established franchises. Or look at 2 recent TV hits, ‘Yellowstone’ and ‘Succession,’ weave strikingly similar tales, only tailored to different demographics through congruent themes.

So, what are we heading towards? A future where entertainment is tailored so precisely that it’s practically reading our minds and serving up ephemeral delights?

What does that mean for our requests in the future? Would we be reduced to uttering one prompt: “Give me more value”?

With AI and LLMs, we’re entering an era of ‘machine creativity’. These systems can process and analyze massive amounts of data, draw from a vast pool of existing content, and generate responses tailored to individual user needs. They don’t just mimic human instinct; they go a step further by making data-driven decisions that can predict and cater to our needs with astounding accuracy.

Is there room for disruptive human creativity in this new landscape? Perhaps. But as LLMs continue to improve and evolve, these instances will become increasingly rare, and more importantly, they may not be necessary. After all, if a machine can fulfill our needs and desires based on our own behavior and preferences, do we need the occasional disruptive idea?

As we stand on the cusp of this new era, we may need to reassess our long-held notions about creativity. Is creativity really about originality, or is it about delivering value in the most effective and satisfying way possible? Is our pursuit of creativity overrated, particularly when AI systems are capable of delivering more value with greater efficiency?

Perhaps, in the end, we’ll find that ‘Give me more value’ is the most creative prompt we could ever ask for. It’s a directive that has the potential to render traditional creativity redundant, replacing it with a more accurate, efficient, and user-centric approach to satisfaction and fulfillment. And who knows? We may find that this approach fulfills us in ways we never thought possible.

As we navigate this transition, I’m not sure if any of this will be true, but one thing remains certain: the paradigms of entertainment and creativity are shifting. How content is crafted, delivered, and consumed might be starkly different in the future than it is today.

Can our behaviors make us creative? Or are we just wandering in an ever-evolving maze of our own creations, no longer needing to come up with anything new? Or are we basically there now?